EAST YORKSHIRE FIELD STUDIES

Number 1 pages 25 - 34

first published 1968

The Jurassic Rocks of the South Cave Area

by F. Whitham and P. J. Boylan

Introduction

The area around South Gave has long been renowned for its fine exposures of Middle and Upper Jurassic rocks. These and their rich variety of fossils have attracted many famous geologists from all parts of the country who, for more than a century, have visited the numerous quarries and other exposures of the area, although in recent years many of the quarries have fallen into disuse and become overgrown or used as rubbish tips.

Summary of Jurassic Strata in the South Cave area

Upper Jurassic

- 8 Oxford Clay about 90 feet of dark grey-blue clays

- 7 Kellaways Rock 10 feet of richly fossiliferous orange-brown sandstone

- 6 Kellaways Sands 45 feet mainly very pure sands, with orange iron-rich bands passing down into sands, shales and clays

Unconformity

Middle Jurassic

- 5 Cave Oolite . 20 feet of oolitic limestone with thin sandy partings

- 4 Basement Beds 5 feet of dark shales

- 3 Hydraulic Limestones 2| 1/2 feet of pale grey limestone

- 2 Lower Estuarine Series 1 foot of fossiliferous sandstone

- 1 Dogger 1 foot of fossiliferous sandstone

Note 1 - “Upper Jurassic" is used here in its pre-1956 sense, the base being taken at the bottom of the Callovian Stage. This is more convenient in Yorkshire than the suggestion put forward by Arkell (1956), and since adopted by the Luxemburg International Colloquium (1962), that the base should be taken at the bottom of the Oxfordian Stage.

Note 2 - "Kellaways Sands" is used here for the group of predominantly sandy rocks, between the Cave Oolite below and the Kellaways sandstone above, following the suggestion put forward by Kent (1955). Prior to this the sands had been arbitrarily divided into Upper Estuarine Series below and Kellaways Sands above.

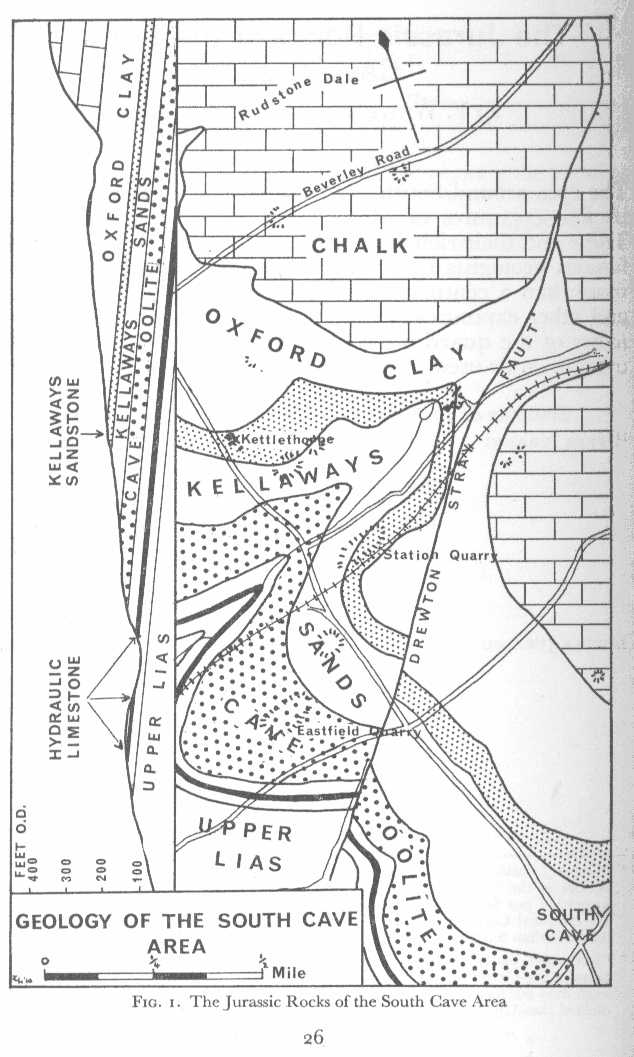

Fig. 1. The Jurassic Rocks of the South Cave Area

Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic succession is poorly exposed and rather complex because during the whole of the Jurassic Period the area was greatly influenced by earth movements affecting the Market Weighton structure. Consequently the Middle Jurassic, which is several hundred feet thick in some parts of England, is here only about fifty feet thick, and many millions of years of deposition are unrepresented.

The Beds Below The Gave Oolite

The lowest Middle Jurassic rock in the area is the Dogger, a very thin buff-coloured sandstone which can be found in the bed of the Ellerker Beck (930297). Above it, yellow-coloured sandy shales of the Lower Estuarine Series have been recorded in temporary exposures. These contain fossils (including plants) and are followed by a fine-grained grey limestone which is probably equivalent to the lower part of the Lincolnshire Limestone. The overlying so-called Basement Beds are occasionally seen in temporary exposures immediately below the Cave Oolite. It is important to note that much more information is needed about all these beds, and that considerable new information may emerge during the building of the proposed Elloughton by-pass.

The Cave Oolite

The only well exposed Middle Jurassic in this area is the Cave Oolite, a predominantly cream or blue-coloured oolitic limestone with occasional partings of clay or sand. This stone has been worked as a building stone for at least 1800 years, and is still seen in use in the walls and the older cottages of the area. It can still be clearly seen in some of the older quarries, notably the Cockle Pits Quarry by the side of the Boothferry Road at Elloughton (944285). Here, on the weathered surfaces can be seen the characteristic "oolitic" structures (small round or oval concretions of lime, called "oolitic" because of their resemblance to the eggs of fish). However, the best localities for examining the Cave Oolite and for collecting fossils are the Eastfield Quarry just south of the disused South Cave station (915325) and at North Newbald (907364). At South Cave the lowest two feet are very variable, but above is a very distinctive hard blue limestone, about 20" thick which is often the lowest bed visible in the quarries. The next bed is a cream-coloured, relatively coarse-grained, fossiliferous oolite which is about seven feet thick. Fragments of fossil wood are relatively common, and plant fronds and echinoids also occur. This is followed by the lower of two sandy partings in the series. The lower parting is a two or three inch thick, orange-coloured, shell-sand in which recognisable fossil fragments are quite common. This is separated from the upper parting by a cream-coloured, shelly oolite in which fossils are quite common although rather difficult to extract. The upper parting is much better from the point of view of fossil collecting since the fossils are found in unconsolidated brownish, shell-sand about one foot thick and are very easily extracted and cleaned. This material is frequently removed from the quarry faces, and is tipped or used for backfilling elsewhere in the quarries. After a few days of rain this tipped material often has many fossil fragments on the surface, so these tips are well worth close examination. The top seven feet of the Cave Oolite is made up successively of a blue-hearted oolite (2 feet thick), a fine-grained grey oolite (2 1/2 feet thick) and a cream coarse-grained oolite (3 1/2! feet thick) and is less fossiliferous. The Cave Oolite fauna is poorly known and careful collecting, recording and identification would be very useful. The small bryozoan Haploecia straminea is very common, and is often the only fossil that can positively be identified in the limestone beds. (In the older literature this is recorded as "Millepora" from which the old name of "Millepore Oolite" was derived.) Bivalves are quite common, although they are sometimes poorly preserved and difficult to identify. They include Ceratomya bajociana, Gervillia sp., Lima sp., "Pecten" sp., and Trigonia sp., Echinoids are relatively common and include Clypeus sp., (somewhat resembling C. ploti), and a species of Stomechinus. Rhynchonellid and terebratulid brachiopods also occur among which is Acanthothiris broughensis of which the Cave Oolite at Brough is the type locality. Ossicles of Pentacrinus and solitary corals also occur, and ostracods (microscopic crustaceans) are very common. No ammonites have been found but the fauna shows that the Cave Oolite is Bajocian in age and is probably approximately equivalent to the Middle Inferior Oolite of the Midlands and the South.

The beds immediately above the Cave Oolite are rarely seen, but are reported to consist of variable sands and clays approximately twelve feet thick, overlain by at least three feet of black shales. Formerly called the Upper Estuarine Series sands, following the suggestion by Kent (1955) they are here united with the overlying thirty feet of beds and regarded as Upper Jurassic Kellaways Sands. Again, any temporary exposures should be very carefully examined and recorded.

Upper Jurassic Kellaways Sands

The best exposure of the Kellaways beds in the East Riding occurs in a quarry which lies parallel to the old railway track (now disused) to the east of South Cave Station (918327). Examination of the beds here shows that the strata underlying the main rock bed are fine white-grey sands which are much more compact in the basal beds where they tend to form a very soft grey rock. Orange coloured ferruginous bands occur towards the top of these sandy beds and contain many fossil casts which are so poorly preserved that it is almost impossible to find a cast which will remain intact. Perfectly round holes also occur in the sand and closer examination will show these to be the hollow casts of belemnites which have been entirely dissolved away. These casts are prominent in the upper part of the sands but are completely absent at the base.

Two rows of large, lime-rich nodules known as "doggers" are present close to the top of the sands and until quite recently an excellent specimen was half exposed in the quarry face. This has now been removed and it will not be possible to see any doggers in this position until further stripping and removal of the sands takes place. A number of these doggers is still scattered about the quarry floor so that examples are available for examination. They consist of an intensely tough, hard limestone and are usually packed with a great profusion of fossils, mostly specimens of the oyster Gryphaea, belemnites and occasional ammonites. The full force of a seven pound sledgehammer is required to break open this extremely hard matrix and although fossils contained in the doggers are beautifully preserved it is very difficult to obtain perfect specimens as they usually fracture during extraction.

The same sandy beds are found on the north side of Drewton valley in the Kettlethorpe Pit (918335) but the doggers as such are absent although large, roughly circular, pieces of limestone rock are seen on the quarry floor. The fauna and the rock which contains the fossils is very similar to the Station Quarry doggers. These sands persist as far as North Newbald and a new pit has recently been opened on the right of the main road (A1034) just before entering this village (912357). Similar beds are exposed here to a depth of 14 feet and are still being excavated. This pit is especially interesting as the doggers are exposed in situ four feet below the top and are of enormous size being about six feet in diameter and two or three feet thick, i.e. roughly three times the size of those found in the Station Quarry. The fossils and the white and grey sands found here are similar to those already described in the South Gave Pit. Numerous nesting sand martins have already moved in and hundreds of nests have been made in the newly exposed face. The birds appear to be oblivious to the noise created by mechanical excavators and the close proximity of workmen. Another small exposure of Kellaways Sands is to be found in a pit in the centre of South Cave village close to the main road near the road junction leading to North Cave but this is not now worked.

Kellaways Sandstone

In the South Cave Station Quarry (918327) the Kellaways Sands are capped by approximately ten feet of dark orange coloured sandstone, the base of which is marked by conspicuous shell beds roughly 15" to 16" apart. The latter are mainly the oyster Gryphaea bilobata and many perfect specimens can be obtained. Numerous casts of lamellibranchs, gastropods, brachiopods and ammonites also occur and can be extracted easily in good condition. In very rare instances the shell itself is preserved, but generally in these beds only the casts remain.

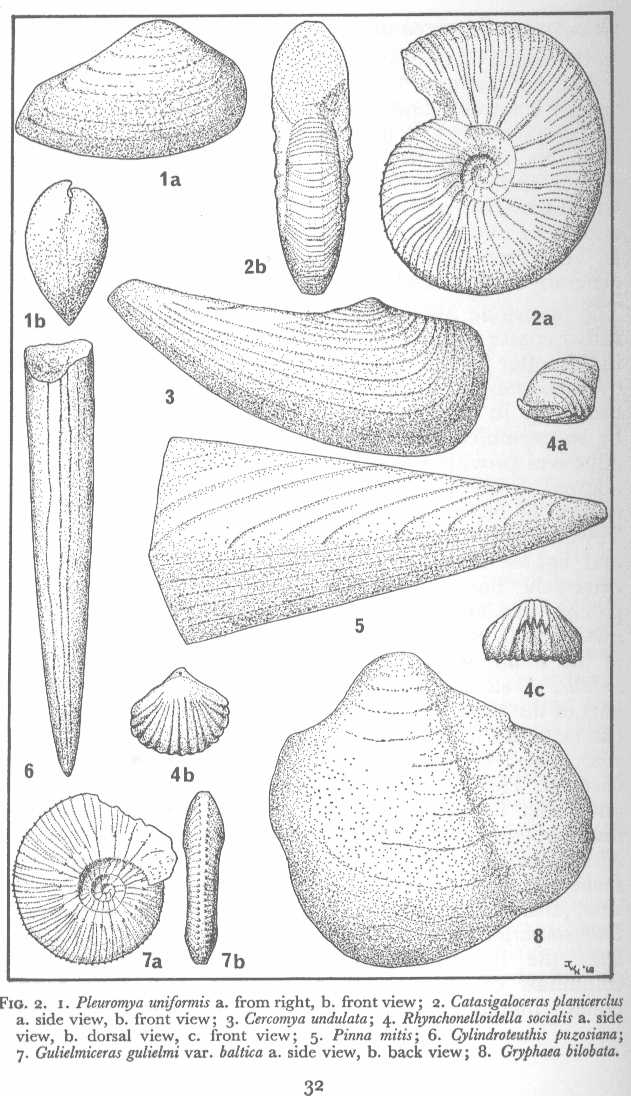

The sandstone above the oyster beds is a solid, massive, rather coarse rock which is softer towards the base and it is in this softer part that very good specimens of the belemnite Cylindroteuthis puzosiana are to be found. Invariably these break up in the process of extraction, but can easily be re-assembled with any of the modern cellulose-based adhesives provided that the edges of the fracture are not allowed to become chipped or damaged. Gryphaea bilobata occurs in great profusion throughout the sandstone. Towards the top the sandstone tends to become harder and lighter in colour, changing in some parts into an extremely hard limestone. These hard, light-coloured patches are amongst the most fossiliferous rocks in the quarry and can usually be identified by an abundance of the small, well-preserved brachiopod Rhynchonelloidella socialis. A sledgehammer is required to break open this part of the sandstone and excellently preserved ammonites can be found which include species of the genera Catasigaloceras, Cadoceras, Proplanulites, Gulielmites, Gulielmiceras, and Choffatia. The nautiloid Nautilus hexagonus has been found and other fossils include the lamellibranchs, Camptonectes lens, Cercomya undulata, Goniomya literata, Gryphaea bilobata, Meleagrinella ovalis, Oxytoma inequivalvis, Pleuromya uniformis, Protocardia crawfordii, Trigonia rupellensis, and species of Area, Astarte, Modiolus, and Pinna; species of the gastropods Bathrotomaria, Dicroloma, Sulcoactaeon, Procerithium and Amberleya; the belemnite Cylindroteuthis puzosiana; serpulae; columnals of the sea-lily Pentacrinus, and rare reptile bones (including Pterodactyl), whilst the brachiopods are represented by species of Ornithella and varieties of Rhynchonelloidella socialis.

The sandstone is not being worked at the present time and the best fossils are found in the large spoil heaps. These are partly overgrown and not very well exposed, so a little digging is necessary to find likely samples of rock.

In the Kettlethorpe Quarry (918335) the sandstone is less massive, tending to be platy, probably due to the action of percolating water over a long period of time. Fossils are not as abundant as in Station Quarry except for Gryphaea bilobata which is excellently preserved and found in large numbers. At the eastern end of the quarry a small stream has cut through the rock leaving behind an infilled sandy section. The erosive action of running water has broken down most of the softer parts of the sandstone leaving the harder lighter coloured parts intact and these can be found in this sandy channel infilling and when broken open are usually packed with good specimens of Rhynchonelloidella, Protocardia, Oxytoma and Meleagrinella. The typical Kellaways ammonites are also found. The North Newbald Quarry (912357) provides a section of some eight feet of dark orange sands with about one foot of thin platy sandstone at the top. The sand contains many casts of Gryphaea bilobata and another oyster also appears to be present in fair numbers. The characteristic double oyster band occurs and the typical ammonite, lamellibranch and brachiopod faunas are fairly common.

Oxford Clay

Almost all the Oxford Clay in the South Cave area is now grassed over except for a thin bed about nine inches thick which, with a little scraping, can be seen above the sandstone at the eastern end of the Station Quarry. During a field trip in August 1965 the Hull Geological Society proved, by augering, about 12 feet of Oxford Clay on the south side of Drewton cutting. Several small sections of the Jurassic worm Hamulus vertebralis were found together with fragments of Oxford Clay belemnites. The typical Oxfordian ammonite Cardioceras has been found on the surface of the field south of the cutting.

Fig. 2. 1. Pleuromya uniformis a. from right, b. front view; 2. Catasigalocerasplanicerdus a. side view, b. front view; 3. Cercomya undulata; 4. Rhynchonellofdella socialis a. side view, b. dorsal view, c. front view; 5. Pinna mitis; 6. Cylindroteuthis puzosiana; 7. Gulielmiceras gulielmi var. baltica a. side view, b. back view; 8. Gryphaea bilobata.

Selected Reading List

ARKELL, W. J. 1956. Jurassic Geology of the World, xvi + 806 pp. Oliver and Boyd Ltd., Edinburgh and London.

BISAT, W. S., PENNY, L. F. and NEALE, J. W. 1962. Geologists' Association Guides No. 11: Geology around the University Towns: Hull. 34 pp. Benham and Co., Ltd., Colchester.

DE BOER, G., NEALE, J. W., and PENNY, L. F. 1958. A guide to the geology of the area between Market Weighton and the Humber. Proc. Yorks. geol. Soc. 31, 157-209.

KENT, P. E. 1955. The Market Weighton Structure. Proc. Yorks. geol. Soc. 30, 197-227.

STATHER, J. W. 1922. On a peculiar displacement in the Millepore Oolite near South Cave. Proc. Yorks. geol. Soc. 19, 395-400.

VERSEY, H. C. 1948. The structure of East Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire. Proc. Yorks. geol. Soc. vj, 173-91.

WILSON, V. 1948. East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. 94 pp. British Regional Geology, H.M.S.O.

F. Whitham, Esq., 2 Samman Close, Broadley Avenue, Anlaby, Hull

P. J. Boylan, B.Sc, Esq., Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

Copyright Hull Geological Society 2016